Shigoto: The Art of Work

How much workspace do you need to produce countless works of art and become a Living National Treasure synonymous with your field?

For Matsuda Gonroku, who lived from 1896 to 1986, it was a room the size of two tatami mats, or roughly six feet by nine. He used a foot-high wood stool placed on the tatami in the middle of the room. It also included some wood cabinets and other work-related items. That’s all Matsuda required to be designated by the Government of Japan as a ningen kokuho, a Living National Treasure, for his lifetime of work as a master of lacquerware.

Image source: National Crafts Museum by Takumi Ota

Image source: National Crafts Museum by Takumi Ota

We recently visited Kanazawa, a beautiful town on the Japan Sea known as “Little Kyoto,” for its celebration of Japanese crafts and traditions. The National Crafts Museum displayed Matsuda’s entire workshop, his tools, and a video demonstrating the quiet magnitude of his craftsmanship and art.

His exhibition is emblematic of a deeply felt cultural expression of shigoto. An everyday word, shigoto translates easily into English as “work.” True enough, but the nuance guides us to something much more powerful.

Image source: National Crafts Museum

Image source: National Crafts Museum

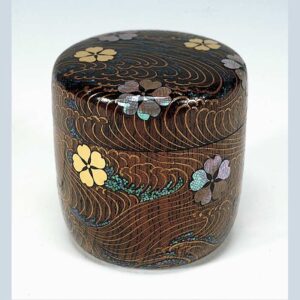

For Matsuda, his shigoto was the step-by-step, layer-by-layer application of a mundane substance—the sap of the lac tree—to produce work of transcendent function and beauty. He excelled at an extraordinarily demanding and complex technique called maki-e, in which pictures, patterns, and letters are drawn with lacquer, and then metal powder such as gold or silver is sprinkled and fixed on the surface.

Image source: https://teshigoto.club/

One look at his workshop shows a man who prized the focused application of energy and materials using a wide variety of highly specialized tools with a blueprint to guide the process. In that sense, Matsuda was an accomplished engineer as much as a gifted artist. Nothing is prized in Japan more than endurance in the face of adversity. Matsuda had plenty of both. There is a price to pay for one’s shigoto. Matsuda’s life spanned the many traumas of the 20th century: Depression, two world wars, postwar devastation, and then the tumult of Japan’s high-growth recovery. But he never stopped. The longevity of his shigoto produced a beauty of its own.

Later that day in Kanazawa, we stumbled onto a completely different kind of “workshop,” a restaurant not much bigger than Matsuda’s studio. No tables, just counter stools. It was operated by a very elderly couple. Everyone called him taisho, meaning master, and she was okaasan, for mother.

We side joked that taisho actually referred to the Taisho period (1912-1926), when the couple opened the place. He was an irascible chef, with hearing issues. But the place was packed. Each new customer slid open the ancient wood door to be greeted with a brusque reason why he couldn’t serve them. The regulars just laughed and waited until taisho relented and let them sit.

The food was good…and fresh. How fresh? Well, the dojo (mud loach) was still wriggling when taisho shoved it into the flour and then offhandedly tossed it into the hot oil. When Mayumi paid the equivalent of $20, okaasan patted her on the arm. “Thanks again, dearie, for your business.” Even taisho paused to loudly thank us as we slid the door open to leave. We can’t wait for the next time. We know the reception will be brusque. But we’ll wait like the other regulars.

We’re pretty sure the Government of Japan will never designate taisho and okaasan as Living National Treasures. They deserve it. But taisho would reject it anyway.

But the magic of shigoto works the same for all of us—layer-by-layer, meal-by-meal, step-by-step, day-by-day. It points to a very different mindset from the trope of following one’s passion. Living National Treasure or not, they would tell us that shigoto—the art of work—is itself the purpose.

![]()