Want to Transform Yourself? Catch The Great Wave

Hokusai is having a moment. Again.

How do we know? Well, if you’re the ukiyo-e artist Hokusai (1760-1849), one sign is having your “Great Wave Off Kanagawa” print auctioned at Christie’s for $2.8 million.

Cool, but it’s hardly his first bow in the global spotlight.

Back in the late 19th century, Hokusai helped set off a huge “Japan” boom in Europe, reminiscent of the current manga and anime craze. His exerted dramatic influence on Impressionists such as Monet, Manet, Degas, van Gogh, and Debussy. Monet plastered his house in Giverny with hundreds of Japanese ukiyo-e prints, many of which were by Hokusai.

We get it. We’re star-struck Hokusai fans ourselves, having just spent six months in Japan, where we went on several Hokusai pilgrimages. We visited two superb museums. One is located at Hokusai’s birthplace in the Sumida district of Edo (current-day Tokyo). The other is in Obuse in Nagano Prefecture, where a wealthy patron commissioned Hokusai to do a magnificent painting on the ceiling of a Buddhist temple. If you’re planning a trip to Japan, both museums are worth a visit.

For us, what makes Hokusai so inspirational was his implacable belief in the art of shigoto—doing one’s work—to the very end. He lived a long life—almost 90 years—at a time when longevity was an extreme rarity. He kept going until the very end.

There’s another ingredient that makes Hokusai’s artistic recipe even more delicious. He showed an unending appetite to reinvent himself through creative transformation.

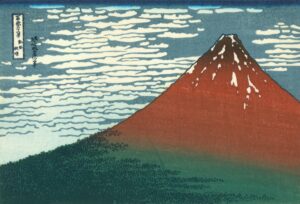

Let’s start with The Great Wave. Hokusai was just getting started on a new creative burst when he produced The Great Wave, as part of his monumental “Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji” woodblock print series. He was already 71 when he started the series that sealed his global renown.

He went to great lengths, literally, to do his work. In his 80s, Hokusai made the 300-mile roundtrip from Edo to Obuse four times on foot. That travel was merely the price to pay for the more demanding work of actually painting the temple ceiling. By contrast, we took the Hakutaka (“White Hawk”) bullet train. It took about 90 minutes, was very comfortable, and included a delicious bento box lunch.

Hokusai’s dedication is all the more impressive in light of the physical and artistic tragedies he faced in life. He was literally struck by lightning—twice! A fire destroyed his studio when he was 79, and much of his early work was lost. A stroke reduced his capacity to work. But he kept a rigorous schedule of physical rehabilitation. Hokusai was extremely fortunate with his youngest daughter, Oi, and he came to rely on her for life and art.

So, it’s no wonder that Hokusai resorted to “exorcism” later in life. Every morning he would draw a Chinese lion or lion dancer and then throw it out of the window to ward off bad fortune. A number of these “morning exorcism” drawings still exist, thanks to his daughter, Oi, running out of the house to collect them and sell them to pay the bills. They are among his most lively and charming works. As the father of two daughters, I can easily imagine her muttering, “Crazy old man!” Funny, because that’s exactly how Hokusai thought of himself. This is the period of his life when Hokusai identified himself as “Old Man Crazy to Paint” (画狂老人: Gakyō Rōjin).

His dedication and resilience yielded an amazing output. By the time of his death, Hokusai had produced 30,000 works of art.

In a fortunate twist, Hokusai was also a master of identity change. He used over 30 signatures in his career, each one representing a new stage of his artistic identity.

One of those signatures was “Iitsu.” When Hokusai turned 60, an important milestone in the East Asian tradition of five cycles of 12 “animal” years (e.g., Year of the Tiger), he created an ambitious new name with a play on words—let’s do it again. He was excited to repeat a second calendar cycle of 60 years.

Hokusai moved in and out of different artistic genres and styles like a manga shapeshifter. He “suffered” from having too many adoring students. To save his precious time and appease his creditors, Hokusai created a brilliant series of textbook manga designed to help his students learn the basics, by using very simple but effective techniques capturing everyday scenes, often with a touch of humor. Edgar Degas drew upon Hokusai’s manga—thousands of sketches of fish, sumo wrestlers, geisha, and everyday urbanites—as the inspiration for his memorable depictions of women in fin-de-siècle Paris.

This device of identity change is something for each of us to consider today. James Clear, author of Atomic Habits, outlines a strategy for creative transformation that Hokusai brilliantly employed two centuries ago.

“….you can’t get too attached to one version of your identity. Progress requires unlearning. Becoming the best version of yourself requires you to continuously edit your beliefs, and to upgrade and expand your identity.”

Hokusai took that to heart, literally. Or, maybe Hokusai was simply trying to stay a step ahead of his creditors, of which he had many. He moved over 100 times in his life, often leaving his dwellings in total shabby neglect.

Hokusai’s life motto might have been, “Die Broke!” or “Go for Broke!” We’ll let you choose.

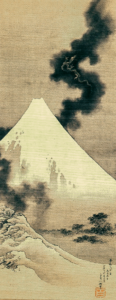

Either way, he imagined his earthly exit as only Hokusai could, in a painting titled “The Dragon of Smoke Escaping from Mt Fuji.” And what a magnificent exit it was—a dragon ascending to the heavens on a plume of smoke from Japan’s sacred mountain. He depicted the ultimate creative transformation—from dying earthbound artist to an immortal heaven-ascending dragon.

What more could he have possibly hoped to achieve? Well, on his deathbed, Hokusai famously bargained for more time to do more work. “If only Heaven will give me just another ten years … Just another five more years, then I could become a real painter.”

It’s exciting to think about what Hokusai might have done with those 10 years. But 90 was enough for Hokusai to do his shigoto and capture the world’s imagination, time and time again.